Birders sometimes do ridiculous things, for apparently ridiculous reasons. I’m a birder, and I am guilty of ridiculousness. The latest episode of this occurred last month, when a friend and I tried to see as many species of birds in Saskatchewan as we could in 24 hours. I had just wrapped up leading The Great Canadian Birdathon for Nature Saskatchewan, but wanted to do something more…intense. A Big Day. A real midnight-to-midnight Big Day. Maybe even taking a run at the provincial Big Day record. That was the thing to do. I met my good friend, James Villeneuve (@jimmynsw), for coffee and pitched to him that this was a good idea. He’s also a birder, so I suppose I shouldn’t be too surprised that it didn’t take much convincing.

Photo credit: Gabriel Foley

We picked a date, May 24, based on our schedules, the weather, and the expected migration patterns of birds. Then we began researching our route. We needed a route that would take us to places to identify as many potential bird species in as short a time as possible. We pored over maps and books and listservs and eBird, and eventually decided that the thing to do would be to start in the boreal forest, in Prince Albert National Park specifically, and work our way down to the pine forests of Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park, a mere 1,200 km away. We also coded the likelihood of detecting each species from 1-5, where 1 represented certainty and 5 impossibility. Finally, we picked a team name, the Nightjarheads (brainchild of Erin Baerwald, @girlborealis), and James even designed and printed team booklets for us!

Photo credit: Gabriel Foley

We left for Prince Albert NP the afternoon of the 23rd, and arrived in time for a couple of hours of scouting. Ideally, we would have liked to have spent at least a few days scouting things out, but both our time and financial budgets for this trip were limited. On the drive north, our excitement was difficult to contain. We didn’t dare say it out loud, but both of us were thinking about the possibility of tackling the existing provincial record. Using our likelihood codes, we had come up with the idea that 150 species was nearly guaranteed, 180 was a solid goal, and that 200+, a near perfect day, was within our reach. Tom Hince and Paul Pratt set the current Big Day record for Saskatchewan of 202 species on June 1, 2008. We danced around actually verbalizing breaking the record – it felt as though saying it would be jinxing it – but we discussed every possible way we could exceed the lofty 202 mark. Expectations were high.

Photo credit: James Villeneuve

At 22:00 on May 23, we began scouting for owls. We drove park roads, stopping every 0.5 km and listening for 3 minutes, then continuing down the road. We found a pair of calling Barred Owls within the first 30 minutes and marked their location with my GPS. We would return after midnight to add them to our list. Finally, my watch hands both pointed directly at the 12, and we officially started our Big Day.

The first bird was a White-throated Sparrow singing, followed by Common Loon, Sora, and then our marked pair of Barred Owls. We continued listening for owls, rushing back to the warmth of the car after each stop. The night was calm, but clear and chilly. We heard a distant Boreal Owl calling, then strained to hear what was almost certainly a Great Gray Owl. We stopped breathing, listening for the deep hoots, but it was too far to ID with certainty, so we let it go and moved on. We added Wilson’s Snipe, Le Conte’s Sparrow, and Swamp Sparrow before the grey light of dawn appeared. Once there was enough light to see, we started walking down the park’s Bog Boundary Trail. We heard Ruby-crowned Kinglets, American Robins, and Cedar Waxwings singing, and then! A Great Gray Owl called. The low hoots thumped into us and we both froze midstep, eyes wide and smiles broad. We silently high-fived then continued down the trail.

Photo credit: James Villeneuve

The forest was oddly quiet for the crack of dawn. The lack of auditory competition made identifying each song straightforward, but it was disappointing. This was the two-hour period, from 4:00-6:00, when we expected to get the lion’s share of our birds. The minutes ticked by, but the birds never showed up. By 6:00, our list only held 42 species. We had hoped to be well over 100 by then. We did hear a pair of Sandhill Cranes, a few Bay-breasted and Cape May Warblers, which was wonderful, had stunning views of a Spruce Grouse trio, heard a single Winter Wren belting out his song, and saw a Brown Creeper marching up a tree trunk. However, there were no vireos, flycatchers were represented by a single Eastern Phoebe, and most of the warblers were absent. Even finding a Common Raven took until nearly 7:30 that morning. It seemed we had, unfortunately, mistimed the bulk of migration.

We left the park, but decided to break our tight schedule and make a 10-minute stop at a creek flowing under the road. There the species we added included Blue Jay, Black-and-white Warbler, and a calling Pileated Woodpecker. A few minutes later, a Sharp-shinned Hawk glided across the road and into a yard. By the time we had left the boreal forest, our species tally was up to 76, which included most of the waterfowl we were likely to get.

Photo credit: James Villeneuve

We pressed on to Saskatoon, where we made our biggest blunder. Each stop, and the drive to it, was precisely timed. We couldn’t afford not to follow our schedule, or we wouldn’t reach our final destination in time to find the target species. However, what was supposed to be a 5-minute stop at a power station to check for gulls turned into nearly half an hour. I had misread the map during planning, and the route to the station was much longer than anticipated. We did pick up the day’s only Spotted Towhee there, but the long shot gulls we were crossing our fingers for weren’t around.

At 10:15, an overhead Peregrine Falcon became our 100th species. We celebrated entering triple digits with a high five, but we knew that 200+ was well out of our reach. It was startling to realize that many common species still weren’t on our list: Marbled Godwit, Wilson’s Phalarope, Horned Lark, Northern Harrier…even Black-capped Chickadee was missing. We had only seen a single Red-tailed Hawk, and Swainson’s Hawks were scarce. Things did not look promising, and our “guaranteed” goal of 150 species seemed awfully distant.

We had settled into a tired silence, but the monotony of empty tilled fields was broken when I shouted at flurry of nonsensical words at James.

“Golden! Stop! Wow! Plovers! Turn! Holy crap! Back there! Plovers!”

Neither of us had ever seen American Golden-Plovers in Saskatchewan, and the stately birds with their bronzed backs, dark bottoms, and disapproving stares blended in almost perfectly with the landscape. I set to counting the flock of a half dozen, no a dozen, no a score, wow, they just keep going, a flock of no less than fifty golden-plovers! I found it difficult to tear myself away from such a terrific sight. James found it difficult to resist pulling out his camera. Although he appropriately reminded me of how behind schedule we were already, and so we then moved on, he has since expressed regrets that the schedule wasn’t sacrificed just a tiny bit more for the sake of a picture or two.

Photo credit: James Villeneuve

The unexpected sighting provided a needed surge of energy and morale boost, and we welcomed the stop at Douglas Provincial Park. We were here to check for two more long shot species, Lazuli Bunting and Yellow-breasted Chat. Neither was present, but we did see a Piping Plover running along the beach, as well as a Common Tern and a Least Flycatcher.

We were now halfway through our Big Day, but only at 109 species. We consoled ourselves that we would pick up some much-needed species at our next stop, where we hoped to find shorebirds. Our hopes were dashed however, when we arrived and found the wind to be fantastically strong. We’d been in the car so much we hadn’t noticed the increase in wind speed, but here it was so strong I had to shout to talk to James. James found a single Red-necked Phalarope near the shore, while I noticed a handful of Western Grebes on the lake. Beyond that, the place was virtually empty. This was a major disappointment, and the stop I’d been looking forward to most on our route. We decided to drive up to a corner of the lake that looked slightly more sheltered, but we weren’t expecting very much. Surprisingly, we found a small mixed-species shorebird flock huddled together. We picked out Black-bellied Plovers, – always a good find in Saskatchewan – Semipalmated Sandpipers, Sanderlings, a Marbled Godwit, and a beautiful flock of Red Knots. Again, neither of us had viewed Red Knots in Saskatchewan and their plump, rosy bodies added a moment of real excitement to the stop.

Photo credit: Gabriel Foley

Our next destination was Grasslands National Park, where we were hoping for prairie specialties like Sprague’s Pipit, Baird’s Sparrow, and Chestnut-collared Longspur. These grassland songbirds are among the fastest declining birds in North America, largely due to the immense habitat conversion of native grass to tame grass or cropland. It was two hours of steady driving before a Wilson’s Phalarope flew overhead and became our 120th tick, and another forty minutes before we entered the park and began to find grassland songbirds. A Chestnut-collared Longspur bobbed across the road and perched on a rock, a Baird’s Sparrow sang from somewhere in a tangle of native grasses, a Golden Eagle drew its wings together and dived towards the ground, and a Bobolink’s song burbled from the male’s black and white flight display, visible a few feet above the ground.

Grasslands National Park is stunning. Westbound tourists often pass by Saskatchewan in a hurry to reach the obvious majesty of the Rocky Mountains, but in doing so they miss the subtle beauty of the grasslands. Perhaps this isn’t surprising, but it is unfortunate. Many people, even people born and raised in Saskatchewan, don’t realize the significance of native prairie to the ecosystem. The grasses and the wildlife evolved together here, and the mosaic of native grass species provide a structure and function that introduced grass species can’t. A field of grass is not just a field of grass, and a visit to a hayfield compared to unbroken prairie will provide an obvious, visual demonstration of this. Grasslands National Park, managed for decades by local ranchers, is one of the most outstanding representations of native landscape in the country and well worth a visit.

Photo credit: James Villeneuve

We moved on from the park, collecting check-marks for Loggerhead Shrike, Say’s Phoebe, Lark Sparrow, and Lark Bunting as we left. We cruised the poorly maintained highway to Eastend, and intercepted a lone Ferruginous Hawk carrying a Richardson’s ground squirrel. We added Long-billed Curlew, Gray Partridge, and Eurasian Collared Dove, but struck out on Cinnamon Teal. We then climbed a series of gravel roads to an outstanding vista, Jones Peak, named after a local palaeontologist. We hoped to find Rock Wren, Violet-green Swallow, and perhaps a Prairie Falcon, but the incredibly strong winds made that impossible. I saw a small bird flit in between some rocks. It was quite possibly a Rock Wren, but I couldn’t be sure and eventually we abandoned the site.

Photo credit: James Villeneuve

It was growing dark when we finally reached Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park. We heard a Common Yellowthroat singing, a Black-capped Chickadee called, and we flushed a Northern Flicker. As the sun faded behind the pine-covered hills we began to search for owls, just as our search had begun nearly 24 hours earlier. Despite our effort, we failed to turn up any new species and Northern Flicker was sealed in as our final species of the day, landing us at 135 species.

Photo credit: James Villeneuve

We certainly fell short of our goal of 150 species, and failed laughably at any attempt at breaking 200 species, but it didn’t really bother us. Sure, seeing more species (and more individuals of those species…) would have been wonderful, and that was the goal we set out to accomplish. But ultimately, the adventure was deeper than that. It was about two friends doing an activity together that they enjoyed, and doing it to the max. We’ve already begun preliminary plans for another try, perhaps even one without an inland cyclone. It’s something that we’ll remember for a long time, one of those ridiculous things birders occasionally do, and for an apparently ridiculous reason: why not?

Photo credit: James Villeneuve

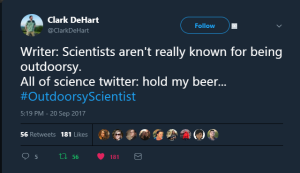

beer…”. Bob Berwyn begins his DW article on climate change and tourism by saying, “Scientists aren’t known for being the most outdoorsy types”. This statement may be true, since

beer…”. Bob Berwyn begins his DW article on climate change and tourism by saying, “Scientists aren’t known for being the most outdoorsy types”. This statement may be true, since